Maria noticed a slight fullness in her neck one morning while applying makeup. Over several months, the swelling became more visible, and she began feeling as though her collar was too tight. When she finally visited her doctor, an ultrasound revealed an enlarged thyroid gland—a condition known as goiter. Like Maria, millions of people worldwide experience thyroid enlargement, often without understanding what it means or when to seek care. This guide walks you through the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and full spectrum of treatment options for goiter, empowering you to recognize when your thyroid needs attention and what steps to take next.

1. Goiter at a Glance: Thyroid Enlargement Explained

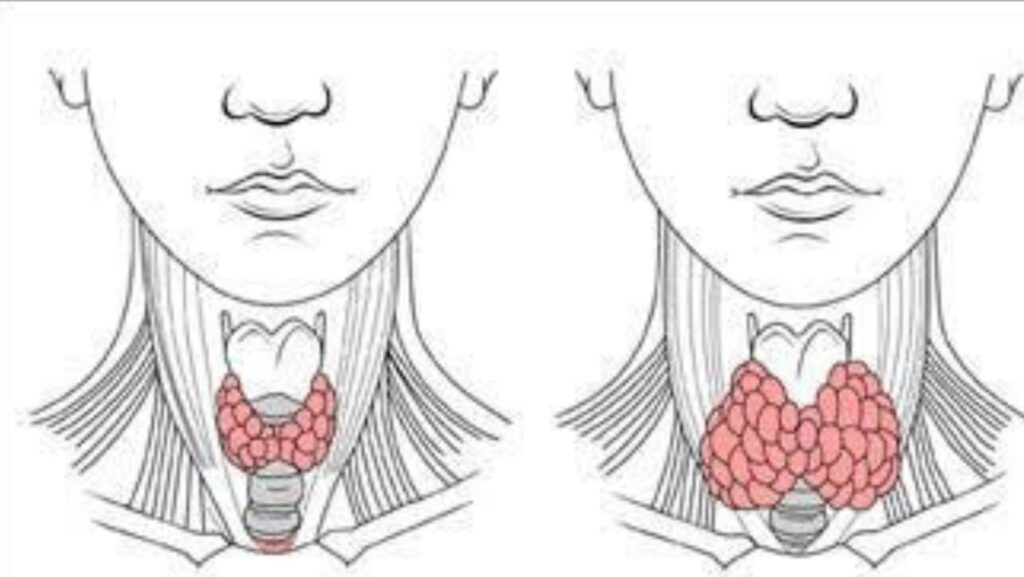

Your thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland that sits at the base of your neck, just below the Adam’s apple. It produces hormones—primarily thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)—that regulate metabolism, heart rate, body temperature, and energy levels. When the thyroid grows larger than normal, the enlargement is called a goiter. Size can range from barely palpable to visibly protruding, and the gland may expand uniformly or develop discrete lumps called nodules.

Goiter affects women more often than men, especially after age 40. Family history of thyroid disease, living in iodine-deficient regions, and autoimmune conditions all raise your risk. Worldwide, iodine deficiency remains the leading cause; in iodine-sufficient countries like the United States, autoimmune thyroid disease and nodular growths are more common triggers.

2. What Causes Goiter?

Understanding why your thyroid enlarges is the first step toward effective treatment. Multiple factors can prompt the gland to grow, and often more than one cause is at play.

2.1 Iodine Deficiency

Iodine deficiency remains a leading cause of goiter in many parts of the world. Your thyroid needs iodine to make hormones; when dietary iodine is scarce, the gland compensates by enlarging to capture more of the trace element from your bloodstream. In regions without iodized salt or access to seafood and dairy, endemic goiter is still widespread. Even in developed nations, restrictive diets and reduced salt intake can leave some individuals at risk.

2.2 Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases

Autoimmune thyroid diseases like Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can lead to goiter by altering hormone production. In Graves’ disease, antibodies overstimulate the thyroid, causing it to swell and churn out excess hormone—a state called hyperthyroidism. In Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, immune cells attack thyroid tissue, triggering inflammation and eventual hormone underproduction (hypothyroidism). Both conditions can enlarge the gland, though the mechanisms differ.

How autoimmunity shifts hormone levels: Graves’ pushes the thyroid into overdrive; Hashimoto’s gradually slows it down.

2.3 Thyroid Nodules and Multinodular Goiter

Benign thyroid nodules are extremely common, especially with aging. Over time, multiple nodules may form—a condition called multinodular goiter. These lumps are usually noncancerous and may produce normal, excess, or insufficient hormone depending on their autonomy. Even when hormone levels remain normal, the sheer bulk of nodular tissue can cause noticeable swelling and local pressure symptoms.

2.4 Other Causes

Thyroiditis (inflammation from infection or autoimmunity), pregnancy and postpartum hormonal shifts, certain medications (amiodarone for heart rhythm, lithium for bipolar disorder), genetic predisposition, and prior neck radiation all increase goiter risk. Identifying the specific trigger in your case guides treatment strategy and prognosis.

3. Symptoms and Complications to Watch For

Many people with small goiters feel nothing at all. As the gland enlarges, however, local and systemic symptoms emerge.

3.1 Visible and Local Symptoms

Neck swelling is the hallmark sign—you or others may notice a lump or fullness at the base of your throat. A feeling of tightness, trouble swallowing (dysphagia), and hoarseness can develop when the goiter presses on the esophagus or recurrent laryngeal nerve. Some patients describe a choking sensation or difficulty wearing necklaces and buttoned collars.

3.2 Systemic Symptoms from Hormone Imbalance

When goiter coincides with hyperthyroidism, you may experience palpitations, heat intolerance, unintended weight loss, anxiety, tremor, and insomnia. Conversely, hypothyroid goiters bring fatigue, cold intolerance, weight gain despite normal eating, dry skin, constipation, and brain fog. Recognizing these systemic clues helps clinicians pinpoint whether your thyroid is overactive, underactive, or functioning normally despite its size.

3.3 Compression Risks

A large multinodular goiter may compress the trachea and cause breathing difficulties, especially when lying flat or during exertion. Stridor (a high-pitched wheeze) signals significant airway narrowing and warrants urgent evaluation. Rarely, compression affects the esophagus (swallowing trouble) or recurrent laryngeal nerve (voice changes). Substernal extension—when the goiter descends behind the breastbone—can hide the true size and complicate surgical access.

4. Types of Goiter

4.1 Diffuse vs. Nodular Goiter

Diffuse goiter features uniform enlargement without discrete lumps; Graves’ disease often presents this way. Nodular goiter contains one or more palpable or ultrasound-visible nodules. A single nodule is called a solitary thyroid nodule; multiple nodules constitute multinodular goiter. Texture, borders, and vascularity on imaging help distinguish benign from suspicious growths.

4.2 Toxic vs. Nontoxic Goiters

Toxic goiters produce excess thyroid hormone, driving hyperthyroidism. Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goiter fall into this category. Nontoxic (euthyroid) goiters maintain normal hormone levels despite enlargement; these may result from iodine deficiency, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in its early compensated phase, or simple multinodular change with aging. Determining toxicity guides whether antithyroid drugs or radioactive iodine therapy is appropriate.

5. How Goiter Is Diagnosed

5.1 History and Physical Exam

Your doctor will ask about neck swelling onset, swallowing or breathing trouble, voice changes, family history, and symptoms of hyper- or hypothyroidism. Palpation of the neck assesses gland size, texture, and the presence of nodules. Red flags include rapid growth, a firm or fixed mass, hoarseness, and enlarged lymph nodes—all of which raise concern for malignancy.

5.2 Thyroid Labs

Blood tests measure thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free T4, and sometimes free T3 to confirm whether your thyroid is overactive, underactive, or normal. Thyroid antibodies—thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO) and TSH-receptor antibody (TRAb)—help pinpoint Graves’ disease versus Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. These labs are foundational; they tell you not just that you have a goiter, but why your gland is enlarged.

5.3 Imaging and Biopsy

Ultrasound is the first-line imaging tool. It characterizes nodule size, borders, echogenicity, calcifications, and vascularity—features that stratify cancer risk. When a nodule meets size and sonographic criteria for concern, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy samples cells for cytology. FNA is quick, minimally invasive, and highly accurate for ruling in or out malignancy.

When to add CT/MRI and airway evaluation: Substernal extension or airway compression may require cross-sectional imaging and direct laryngoscopy to assess tracheal patency and vocal cord function.

6. Treatment Options: From Watchful Waiting to Thyroidectomy

The right treatment depends on goiter size, symptoms, hormone status, and nodule characteristics. Options span observation, medication, radioactive ablation, and surgery.

6.1 Watchful Waiting

Small, asymptomatic, euthyroid goiters often need only periodic monitoring. Your endocrinologist will recheck thyroid function and ultrasound every 6–12 months to ensure stability. This conservative approach avoids overtreatment while catching any growth or functional change early.

6.2 Medications

Levothyroxine (synthetic T4) is prescribed for hypothyroid goiter caused by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or iodine deficiency; it replaces missing hormone and may modestly shrink the gland over time. Antithyroid drugs like methimazole block hormone synthesis in hyperthyroid goiters, including Graves’ disease and early toxic multinodular goiter. Where dietary iodine is insufficient, supplementation can prevent and sometimes reverse endemic goiter.

Who benefits—and who should avoid—iodine supplements: Supplementation helps in true deficiency but can worsen autoimmune thyroid disease, trigger hyperthyroidism in autonomous nodules, and requires caution during pregnancy. Always consult your doctor before starting iodine.

6.3 Radioactive Iodine Therapy

Radioactive iodine (I-131) is a targeted treatment for toxic multinodular goiter and Graves’ disease. Thyroid cells absorb the radioactive isotope, which then destroys overactive tissue from within, reducing both hormone excess and goiter size. The procedure is outpatient, though temporary isolation precautions apply. Most patients eventually become hypothyroid and require lifelong levothyroxine, but symptoms of hyperthyroidism and compression resolve.

6.4 Thyroidectomy (Surgery)

Thyroidectomy is recommended for large goiters causing compression, cancer suspicion on FNA, or cosmetic concern. Surgeons may remove one lobe (lobectomy) or the entire gland (total thyroidectomy) depending on disease extent. Key surgical risks include injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (voice changes) and hypoparathyroidism (low calcium). Recovery typically takes 1–2 weeks; long-term, most patients require thyroid hormone replacement.

Treatment options for goiter range from iodine supplementation to thyroidectomy, depending on the underlying cause. Decision factors include symptom severity, hormone levels, nodule cytology, patient preference, and surgical candidacy.

7. Diet and Lifestyle Support for Thyroid Health

7.1 Iodine Intake Guide

Adults need approximately 150 micrograms of iodine daily; pregnant and breastfeeding women require 220–290 micrograms. Iodized salt, seafood (cod, shrimp, seaweed), dairy products, and eggs are rich sources. Supplements can help if dietary intake falls short, but excess iodine can trigger thyroid dysfunction, so stick to recommended doses and avoid kelp or high-iodine supplements without medical advice.

7.2 Selenium, Zinc, and Goitrogens

Selenium supports thyroid hormone metabolism and may reduce thyroid antibodies in autoimmune disease; Brazil nuts, fish, and whole grains provide selenium. Zinc aids hormone synthesis; sources include meat, shellfish, legumes, and seeds. Goitrogens—compounds in cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, kale) and soy—can interfere with iodine uptake when consumed raw in very large amounts, but moderate cooked intake poses no risk for most people.

7.3 Lifestyle Factors

Smoking introduces thiocyanates that impair iodine transport, worsening goiter risk—quitting helps. Maintaining a healthy weight reduces metabolic strain on the thyroid. Managing stress through mindfulness, exercise, and adequate sleep supports hormonal balance and may ease symptoms of thyroid dysfunction.

8. When to Seek Care—and Urgent Signs

8.1 Prompt Evaluation

If you notice neck swelling or trouble swallowing due to goiter, seek an endocrinology evaluation promptly. Early assessment clarifies whether treatment is needed and prevents progression. Urgent symptoms—breathing difficulty, stridor, rapid enlargement, or a hard, fixed neck mass—demand immediate medical attention, as they may signal airway compromise or malignancy.

8.2 Special Situations

Pregnancy requires optimized thyroid levels before conception and throughout gestation to support fetal brain development; uncontrolled hypo- or hyperthyroidism increases miscarriage and preterm birth risk. Pediatric and adolescent goiter can affect growth, school performance, and emotional well-being, so timely diagnosis and treatment are critical during these formative years.

9. Your Care Pathway at Liv Hospital

9.1 Multidisciplinary Thyroid Care

Liv Hospital brings together endocrinologists, head and neck surgeons, radiologists, and nuclear medicine specialists to deliver coordinated, evidence-based goiter care. From initial consultation through long-term follow-up, our teams collaborate to tailor evaluation and treatment to your unique clinical picture, ensuring seamless transitions between observation, medical therapy, and surgery.

9.2 What to Expect

Your visit begins with a comprehensive history and physical exam. Same-day thyroid ultrasound and blood work expedite diagnosis, and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration is available when nodules require biopsy. For hyperthyroid goiters, our nuclear medicine department offers radioactive iodine therapy with clear safety protocols. When surgery is indicated, our experienced thyroid surgeons perform thyroidectomy with intraoperative nerve monitoring and careful parathyroid preservation, minimizing voice and calcium complications. Structured follow-up tracks hormone levels, monitors for recurrence, and adjusts replacement therapy as needed.

10. FAQs About Goiter

10.1 Is a Goiter Cancer?

Most goiters are benign. Fine-needle aspiration and ultrasound risk stratification help identify the small percentage of nodules that are malignant or require surgical removal for definitive diagnosis.

10.2 Can a Goiter Go Away on Its Own?

Size may stabilize or shrink with iodine repletion in deficiency-driven goiters, or with thyroid hormone therapy in Hashimoto’s. Large, nodular, or compressive goiters typically require intervention—medication, radioactive iodine, or surgery—to reduce size and relieve symptoms.

10.3 Will Treatment Affect My Voice or Calcium Levels?

Thyroidectomy carries a small risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (voice changes) and hypoparathyroidism (low calcium). Expert surgeons using nerve monitoring and meticulous technique minimize these risks; most patients experience no permanent complications.

10.4 Is Radioactive Iodine Therapy Safe?

Yes. Radioactive iodine is a well-established, targeted treatment. Temporary isolation precautions last a few days; long-term cancer risk is minimal. Pregnancy must be avoided for 6–12 months after therapy, and fertility generally returns to baseline thereafter.

10.5 Costs and Coverage

Goiter workup includes office visits, laboratory tests, ultrasound, possible FNA, and treatment (medication, radioactive iodine, or surgery). Most insurance plans cover medically necessary thyroid care; prior authorization may be required for imaging and procedures. Contact your insurer early to understand copays, deductibles, and out-of-pocket maximums.

Goiter is a common, treatable condition. Recognizing symptoms early, understanding your diagnostic options, and partnering with an experienced thyroid care team ensure the best outcomes. Whether you need simple monitoring, medication adjustment, or surgical intervention, expert guidance tailored to your specific cause and clinical picture will restore thyroid health and improve your quality of life.